Key takeaways:

- Third quarter growth decelerated as a slew of factors – namely a resurgent virus and continued supply chain bottlenecks – held back the economic recovery. As these issues recede, the economic is expected to reaccelerate in early 2022.

- Inflation accelerated during the period as strong consumer demand met with widespread supply chain shortages. Labor shortages also contributed to wage inflation, which has the potential to ignite longer-term inflation pressure.

- The Fed signaled it would begin withdrawing pandemic-era monetary support by year end as it sees significant healing throughout the economy and may be closing in on its long-standing inflation targets.

- While inflation associated with economic reopening will likely persist through next year, we believe it will ultimately open the door for more normal interest rate policy. Rain portfolios are well prepared to weather that process.

- Generally, Rain portfolios have enjoyed solid relative performance vs. benchmarks in 2021.

Market Update:

Toward the end of the third quarter of 2021, it became clear the economic rebound in the US would be more uneven than expected. A resurgent virus and signs of waning vaccine effectiveness held back the nascent recovery in the travel and leisure industries, supply-chain bottlenecks persisted and began to hamper production, a regulatory crackdown in China sent shudders through foreign markets, and back-to-back hurricanes in the eastern US further complicated the recovery. The effect on the economy was not unlike the deceleration seen during the virus surge in early 2021. However, unlike that hiccup, Q3 was marked by a sharp uptick in consumer prices and indications from the Fed that it would begin withdrawing monetary support. After more than 225 days of relatively calm markets, equities became notably more jittery as the quarter came to an end. While the bumpy economic restart is not particularly surprising, looking through the recent noise the US economy remains on solid footing, and we would expect it to gain steam again as the latest wave of COVID passes. That said, inflation and the prospect of higher interest rates will continue to dominate headlines in the coming months and may contribute to equity market volatility in the near term.

As we discussed in our most recent communication, inflation has accelerated significantly this year as strong consumer spending outpaced the economy’s ability to produce goods, with supply shortages across most major sectors of the economy. Year-over-year measures of the consumer price index (CPI) have exceeded 5% since the beginning of the summer (albeit from very low levels at the outset of the pandemic). Many price increases can be traced to temporary supply chain issues. This is most evident in the global shortage of semiconductors which has contributed to higher prices across a wide range of products, including cars. Higher commodity prices have also contributed to the issue as has the recovery in prices in hard-hit areas of the economy like air travel, dining, and rents.

Supply shortages tell the short-term (i.e. transient) story about increasing prices, while labor markets may indicate a longer-term (and stickier) problem. As the economy recovers, it has replaced 17 million of the 22 million jobs lost during the recession, bringing the unemployment rate to 5.2%. While the concept of full employment is a moving target, that level is still shy of the pre-pandemic low of 3.5% implying that some slack remains in the labor market. In theory, that slack should keep a lid on wage growth. Wages, however, have been rising at an annualized rate of 4%, a level not seen since the early 1980s.

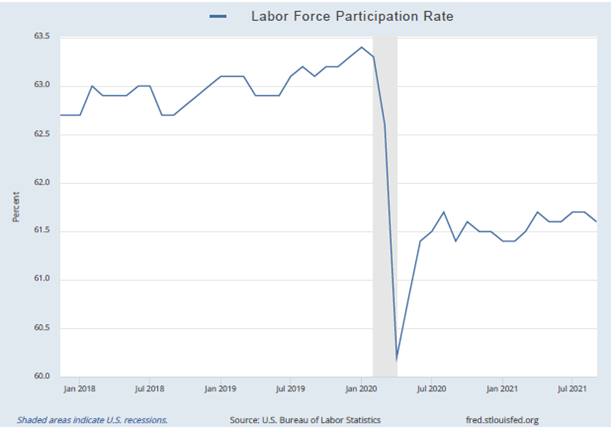

So, what gives? Just as consumer spending has outstripped the economy’s ability to produce goods, it appears that for the time being the economy’s ability to create jobs has outstripped the labor market’s ability to produce workers. In fact, the labor force participation rate remains 1.8 points below its pre-pandemic levels, indicating that there are simply fewer people willing to be employed right now. That difference, in the context of surging labor demand, may explain the wage growth we have witnessed despite the appearance that the economy is operating below full employment. Our expectation is that the labor market is lagging the broader economic reopening due to temporary constraints like enhanced unemployment benefits, declining immigration, more expensive childcare, and persistent fears about the Delta variant. Should labor force participation remain stubbornly low, however, we will be more concerned that recent price pressures could become a longer-term problem.

Markets are justifiably worried about inflation. The basis of these concerns is that rising prices could drive interest rates higher as monetary authorities tighten policy to fight inflationary pressures. Inflation and rising rates can have a number of negative consequences for the recovery including higher mortgage costs, slower economic growth, greater wealth disparity, higher debt service and larger deficits, and the potential that inflation expectations become entrenched over time. Historically, higher US rates have also been devastating for developing countries who rely on cheap capital to finance growth.

On the other hand, however, it is also worth noting that low inflation and ultra-low interest rates come with problems of their own. In the worst case, deflation in a credit-based economy can be devastating for borrowers as the value of their debts increase on a real basis. Low interest rates can also encourage overborrowing, amplifying the effect of recessions, and drive over saving among retirees who are forced hoard capital to make up for a lack of interest income in their portfolios. Finally, ultra-low rates also complicate the central bank’s ability to manage the economic cycle because it lacks the ability cut rates further, one of the most basic tools of monetary policy

That is why policy makers in most developed countries have been bending over backward to create inflation since the Great Recession. For more than a decade, inflation has undershot the Fed’s long-term target of 2% and the central bank has said it will allow inflation to remain above that level for a considerable period time before responding with higher rates. It will treat the 2% target as a floor rather than a ceiling. Hence, even though the Fed’s measure of inflation (the PCE deflator) is exceeding 4% year-over-year, monetary policy remains accommodative, and the Fed is unlikely to move on interest rates until late 2022. The central bank’s September announcement that it would likely begin tapering its bond purchases later this year is simply a reflection of its view that the economic expansion is solid, and that growth, inflation and employment will be on a sustainable path as the economy reaccelerates in early 2022.

In this good inflation / bad inflation dichotomy, fixed income and equity markets have sent mixed signals. The inflation narrative seems to have been used to explain every dip in the stock market since April while over the same period bond yields have largely declined, indicating bond markets are still dismissive of long-term inflation concerns. Traditional inflation hedges like gold and many commodities also fell during the period. More likely than not, markets are reflecting something that we already know, that inflation and its causes are still an extremely inexact science.

We are keeping a cautious eye on the inflation situation because, ultimately, inflation and its impact on interest rates represent one of the most important wildcards facing markets in the near term. At present, we view the advent of inflation as a success of central bank policy and an important precursor to getting to a more normal interest rate environment that has been sorely lacking since 2008.

Portfolio Update:

With few exceptions in financial history, rising rates and moderate inflation have been supportive of equities because they most often occur together during periods of economic growth like we’re experiencing today. Equities tend to be a good store of value in inflationary environments because they are businesses that charge prices and pay wages; on a real basis their cash flows have tended to offset the erosive effects of long-term inflation. Our current positioning reflects this reality, with a full benchmark allocation to growth.

Within this framework, however, we are mindful that the market has not seen a meaningful correction in more than a year and that valuations remain stretched in certain areas of the market. We continue to focus on the cheaper parts of the market, preferring managers who focus on value instead of the richly priced growth stocks. (Coincidentally, value stocks generally tend to outperform growth stocks during periods of rising interest rates, so we see this as serving two important purposes.) We are also favoring smaller and mid cap strategies over the ultra-large cap companies whose valuations have been bid up in the past 18 months. Finally, we have been moving portfolios increasingly toward foreign developed markets where valuations have been depressed relative to US equities for more than a decade. Low Correlation Growth strategies are playing an increasingly important role in portfolios as well because of their ability to buffer equity market volatility. On the defensive side of portfolios, we have continued to limit credit exposure in an environment of extremely tight credit spreads. Furthermore, we have taken a somewhat bar belled approach to interest rate exposure, favoring very short-term bond funds for liquidity and some long-term strategies for ballast, avoiding the most volatile middle part of the yield curve.