Key takeaways:

- End of cycle signs are emerging as the Fed grapples with the risks of an overheating economy

- While a slowing economy is likely to preclude the need for sharp interest rate hikes to combat rising prices, the tight labor market could force the Fed’s hand sooner than markets are pricing in

- Higher interest rates, a shrinking central bank balance sheet, labor shortages, higher corporate taxes and a dramatic decline in fiscal support will mean slower earnings growth and more muted returns for equities in 2022

- Rain portfolios generally did well against their respective benchmarks in 2021, but did so with broader diversification and less exposure to the riskiest parts of the market

Market Update:

Despite uneven growth and the start-stop nature of the COVID economy in 2021, the US (and most developed economies) registered the strongest economic growth in nearly four decades. The robust economic activity contributed to a sharp drop in unemployment and strong corporate profits, but also triggered high inflation and undercut the impetus for further fiscal economic support. By year end, bond yields began creeping upward and the Fed had shifted to a distinctly more hawkish tone after initially dismissing inflation pressure as “transitory.” In this environment, 2022 will be a year of transition as the market adapts to tightening monetary policy, the end of large fiscal support packages, decelerating earnings and an uncertain inflation picture. The Fed’s balancing act this late in the economic cycle will be to cool the economy enough to keep inflation in check without triggering a full-blown recession. Equity markets, many parts of which remain expensive despite the rosy earnings picture, will be particularly sensitive to these dynamics.

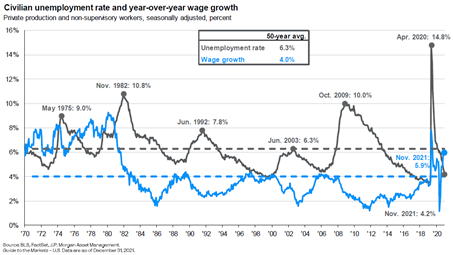

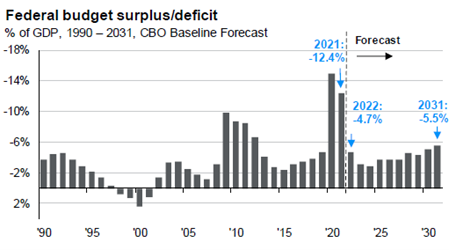

In simple terms, the economy is at risk of overheating. The $5.3 trillion in fiscal support that gushed into the economy over the past two years during an extended period of ultra-low interest rates as well as the post-vaccine economic reopening have led to a sharp economic rebound that returned the economy to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021. In addition, the economy has recovered 18.4 million of the whopping 22.4 million jobs that were lost early in the pandemic; within 4-6 months, the economy is on track to reach full employment. The rapid rebound in the labor market, wage growth and supply chain disruptions have contributed to inflation as high as 7% by year end. While supply chain issues as well as virus variants have acted as a headwind to the red-hot economic recovery in the second half of the year, much of that growth will simply be deferred into the early part of 2022.

A number of factors will weigh on growth as the year progresses and will help bring the economy back to its long-term trend growth of roughly 2% annualized by the second half of 2022. These include higher interest rates, a shrinking central bank balance sheet, labor shortages, higher corporate taxes and a dramatic decline in fiscal support.

This deceleration should do much of the heavy lifting required to keep a lid on inflationary pressures, limiting the need for more radical interest rate policy on the part of the Fed. However, as we approach full employment by mid-year, there is a very real possibility that labor shortages and ensuing wage growth could feed through to higher inflation that is more entrenched than the one-off price increases resulting from supply chain disruptions. In the face of recent wage pressures, businesses have been able pass the extra costs on to consumers. As in previous inflation cycles, labor has responded by seeking further wage increases to offset the higher cost of living.

Should this process of wage bargaining begin to drive longer-term inflation expectations, the Fed will be forced to take more aggressive action. This will take the form of earlier, larger, and more frequent rate hikes than the market is currently anticipating. As it stands now, the Fed is expected to end its balance-sheet tapering program by March of this year and begin raising rates starting in June, with three rate hikes of .25% by the end of 2022. Equity markets and longer-term bond markets so far have shrugged off the recent inflation scare, indicating either investors’ confidence in the Fed’s ability to manage inflation within its 2% target average through monetary policy or a more general faith that the economy will return to healthier (e.g. less inflationary) growth as pandemic effects recede. Should the market begin to doubt this narrative or the Fed’s hand is forced due to incoming data, we would expect the ensuing jump in bond yields to lead to significant equity market volatility.