- Current economic activity is heavily dependent on continued fiscal and monetary support as well as the progression of Covid-19, making for a fragile economic recovery

- The strong rebound in asset prices during the second quarter in the context of poor economic performance has led to stretched valuations in equity markets

- This leaves us with a dangerous disconnect between asset prices and economic fundamentals that could lead to further market instability

- We have used market strength during the quarter to pare back exposures, a cautious stance that we believe will allow us to take advantage of market volatility in the coming months

The second quarter saw broad financial markets rebound strongly, erasing nearly all losses experienced during the March meltdown. Markets were buoyant on the back of unprecedented fiscal and monetary support from policy makers around the world as well as early signs that COVID infection rates appear to be levelling off and may be past peak in some countries. Meanwhile, the economic fallout from mass lockdowns and social distancing measures has been more severe in most countries than originally anticipated. Furthermore, while the pandemic has levelled off in some countries, it has worsened in many others including the United States. The market’s behavior implies expectations of a quick rebound in economic activity to levels seen before the onset of the virus, yet nearly every path forward from here suggests an increasingly difficult climb out. With market valuations at levels last seen during the Dot Com bubble, there is a dangerous disconnect between asset prices, fundamental valuations, and the prospects for economic activity. As such, we have used the recovery in asset prices to scale back exposure and put portfolios in a better position for the next stage of volatility.

As we have discussed in earlier communications, the path out of this economic recession is in large part dependent on continued support from fiscal and monetary policy makers as well as the progression of the disease. This speaks to the fragility of the economic recovery. The early stage of the recovery will have dramatic gains like those seen in the last two months, but this is more a feature of the dramatic stop-start nature of this recession. Future economic gains will likely be more muted as the recovery drags on with lower levels of activity in the context of surging Covid infections. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell put it in uncharacteristically direct words, “Output and employment remain far below their pre-pandemic levels. The path forward for the economy is extraordinarily uncertain and will depend in large part on our success in containing the virus. A full recovery is unlikely until people are confident that it is safe to reengage in a broad range of activities.” Fed Presidents Raphael Bostic, Eric Rosengren, and Thomas Barkin have suggested early data in their respective regions indicate the economic rebound is already stalling, while San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said her best-case scenario is that the economy won’t return to pre-crisis levels for four to five years. The Fed has committed to keeping rates near zero for as long as it takes to regain our economic footing.

The Fed’s unusually dramatic guidance is almost certainly geared toward maintaining a sense of urgency with fiscal policy makers, whose resolve appears to be weakening with the rebound in asset prices and approaching election season. The forthcoming support package intended to extend benefits past the July expiry of the CARES Act is expected to be less than half of the original package. The Fed is hoping to avoid the scenario that played out in the 2008 crisis, during which Congress provided only meager fiscal support and thereby forcing the Fed to bear the brunt of economic recovery efforts through the crude tool of monetary policy (e.g. low interest rates and bond purchases). Extended periods of ultra-low interest rates can themselves create dangerous economic imbalances that the Fed would like to avoid.

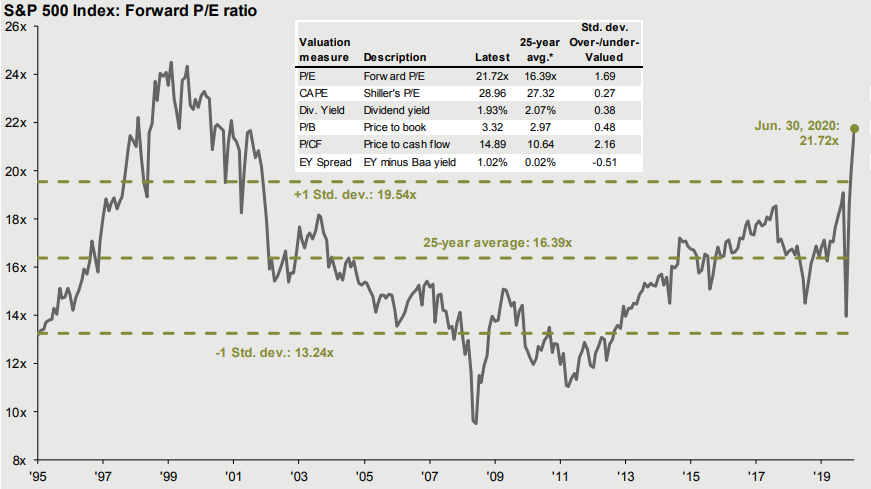

Meanwhile, equity and fixed income markets have been on a tear. Most stock indices are at or near all-time highs while credit markets broadly have retraced about 70% of their initial losses. In the United States the turnaround in asset prices started around March 23 following the announcement of the Fed’s $2.3 trillion credit facility and Congress’ more than $2 trillion CAREs Act. In the absence of strong economic data or improving corporate earnings, the bullish mood among investors remains largely predicated on strong policy support and heretofore declining Covid cases. This has set up a market that is richly valued by historical measures:

The disconnect between asset valuations and the real economy does raise the risk of another correction in asset prices. In the absence of fundamental underpinnings to this rally, any number of reasons could trigger more equity market volatility going forward: The recession could be deeper and longer than currently priced into the market; there could be a second wave of the virus and containment measures (albeit on a more limited basis) could be reinstated; expectations about the extent and length of central banks’ support of financial markets could turn out to be too optimistic; a resurgence of trade tensions could hurt market sentiment; fiscal support could evaporate in the context of an election season; broadening social unrest could also damage market sentiment. The point is that there are myriad ways that an overvalued market can lose its footing and relatively few in this environment that could lend further support to even higher valuations.