- The quick trip down the elevator the economy took in March and April is giving way to a slower and more tedious return up the staircase, dashing hopes of a V-shaped recovery.

- With interest rates near zero, US economic policy is increasingly driven by a fickle Congress, a feature that we expect will contribute to market volatility.

- Broad equity markets remain richly valued at a time that policy uncertainty is at an all-time high; our current portfolio themes tilt toward safety and certainty during this time.

Market Update:

The recovery that took hold in May and June, bolstered by the $2.2 trillion CARES act and aggressive action by the Federal Reserve, began slowing over the summer and more dramatically into the Fall. Roughly 15% of small businesses have already gone under during the recession, the large companies that took government aid like airlines and hotel chains have begun to lay off workers, and state and local governments are following suit as tax revenues dry up. With interest rates at zero, the economy is increasingly dependent on politicians in Congress to provide further support during the unfortunate backdrop of an election year. In the absence of further Congressional support, this will result in further permanent damage to the economy and a significantly longer trajectory out of this recession. Markets, however, are priced for a V-shaped recovery. This sets the stage for further volatility until we have greater consensus for economic support from policymakers and (or), ultimately, a permanent solution to the virus.

The economy has likely already emerged from one of the deepest recessions of the last century. The shelter-in-place orders that led to a collapse in economic activity in March and April have given way to a social distancing economy that has allowed for a limited resumption of economic activity. In many areas, like housing and autos, growth has been better than expected. However, the severity of the recession and the fact that we do not have a permanent solution to the virus means that activity will remain constrained. A big reason for this is that consumption drives nearly 70% of economic output in the US; with many service-sector businesses only partially reopened and with high unemployment constraining households’ ability to spend, the main engine of the economy remains impaired.

It is broadly accepted that during this virus-induced impairment, the economy will need further support from policymakers. In a typical recession, there is a downward spiral in which job losses lead to still lower demand, and subsequent additional layoffs. This dynamic was largely disrupted by the infusion of funds to households and businesses via the CARES Act. Without further Congressional support, it is expected that the slowing pace of recovery will trigger more typical recessionary dynamics, as weakness feeds on weakness. At this point in time, it is unknown if that will result in a full-blown double-dip recession or simply a slower pace of recovery. What is known, however, is that it will result in a more protracted recovery than is desirable from a full employment and price stability standpoint, goals that are near and dear to the Fed’s mandate.

This has prompted unusually dire language from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and various regional Fed presidents, imploring Congress to step up with more aid. The Fed has made it clear that at the lower bound of interest rate policy it has essentially exhausted its most effective policy tool, leaving it with balance sheet operations that have diminishing economic benefits. Furthermore, the Fed has said that it believes its own tools are too blunt to address some of the economy’s most pressing issues facing low-income workers and struggling businesses, for instance. Of particular concern to Chairman Powell is the confluence of policy paralysis in Congress with the expectation that virus cases will surge going into the Fall and Winter months. Powell has warned of tragic economic consequences that will ensue should Congress fail to act soon. In what seemed like an admission of just how few tools the Fed has left at its disposal, Powell said recently “managing this risk will require following medical experts’ guidance, including using masks and social distancing measures.”

While markets still expect some form of stimulus from Congress shortly after the election (or sooner), the fickle hand of Congress – the same body that routinely shuts down the government as a negotiating tactic – as the primary economic policy driver will continue to contribute to market volatility. Since the beginning of the COVID crisis in the US, markets have largely tracked the progress of the disease and the status of federal support for the economy (most everything else just registers as noise when evaluating the underlying risk factors currently driving markets). When that support expired in August at a time when virus numbers began creeping up again across the nation, markets responded predictably with more volatility in September. We expect this dynamic to continue, if not worsen, as fiscal deficits expand, and political divides grow. The days of quick, dramatic, and bipartisan support for the economy that we witnessed in March at the outset of this crisis are a thing of the past.

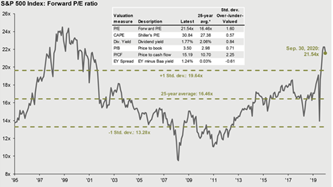

By most measures, the broad equity market appears overvalued. Dividend yields in the US have dropped below their long-run average and the forward price-to-earnings ratio (a measure of how expensive stocks are relative to future earnings) of the S&P 500 at 21.5x is as high as it has been since the late days of the Dot Com bubble:

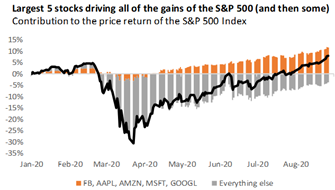

The strong performance this year of equity indices in the face of a devastating recession has given rise to the narrative that stocks are disconnected from the real economy. The reality is a little more complicated, albeit no less concerning. As of the end of Q3, the S&P 500 was up 5.5%. While many companies in the index are in fact struggling – 495 of the 500 stocks in the index are on average in deep negative territory – the companies whose business models and technology have allowed them to thrive during this time account for all of the market’s gains: Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and Google:

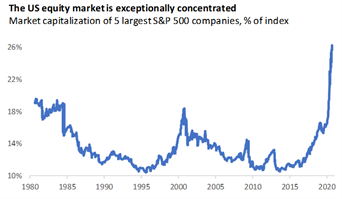

Just five companies account for the lion’s share of market’s gains this year, making the market more concentrated than it has been since the 1960s:

This lack of breadth in market returns has historically been a precursor to broader market corrections; there are simply fewer companies supporting the market so an earnings miss by one of them can have an outsized impact on overall index performance.